“Fellow travelers, this is what you want, this is what you need. This is the path to true happiness and wisdom.”

Anthony Bourdain uttered those words while sitting on a red plastic stool on a street-side restaurant in Vietnam. And for millions of people, we were sitting there with him, sharing that bowl of noodles and late-night beer.

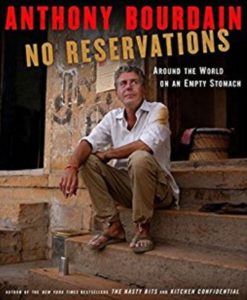

Bourdain looked like a traveler, a real traveler of the old school. His face appeared hewn from rough stone, subjected to every possible angle of the sun’s rays, worn and creased as a trusted map. He certainly stood out wherever he went, ambling through marketplaces and alleys and crowds like a towering, silver-haired golem (in his bestselling Kitchen Confidential, he described himself as “a bony, whippet-thin, gristly, tendony strip of humanity”) and yet was somehow able to melt into his environments, from Alabama to Zimbabwe.

Like many people, I first discovered Bourdain through his show No Reservations. I ordinarily speed past television’s cooking shows, but something made me linger at Bourdain. Was it the “down-to-earth” quality? He certainly did emerge from the trains, planes, and automobiles as a regular dude, casually dressed and with tattoos displayed, feet firmly planted on local soil, hands eagerly dipping into local meals, sipping and drinking and talking and seeing his local environment.

Or was it his barbed, ever-entertaining and thoughtful acumen?

Bourdain’s wit was like some hybrid of Holden Caulfield and Jonathan Swift. He was that rarest and most sincere of cosmopolitans: a true citizen of the world. He ventured to “exotic” places without ever treating them as alien otherworlds. Rather, he met the people behind the dishes, the voices behind the stalls. He traveled to the four corners of the Earth and showed that: My God, it’s full of humans.

No Reservations was a tour-de-force of food and revelation. In one moment, Bourdain is gleefully sipping local noodle soup and rattling off its astonishing ingredients… and the next, he’s discussing how thousands of still-living bodies were buried alive by North Vietnamese troops, or interviewing a man who spent six years of his childhood living underground with the remnants of his village. Anthony Bourdain spoke to–and connected with–human beings, listening to their stories. He laughed with them, he toasted with them, he dined with them.

He was cranky. Gods above, how I adored his crankiness because I understood it. I’ve never been very good about concealing my own disgust at shallowness or bullshit, and Bourdain had a blistering zero-tolerance policy that transcended pop culture ideologies. Just go to his show Parts Unknown, and tune into the Sicily episode when he goes snorkeling. You know the one I’m talking about: when his local hosts drop dead octopuses into the water around him “to be heroically discovered” by them moments later.

“Strangely,” Bourdain says in voice over, “everyone else pretends to believe the hideous sham unfolding before our eyes. For some reason, I feel something snap, and I slide quickly into a spiral of near-hysterical depression… you’ve got to be pretty immune to the world not to see some kind of obvious metaphor.”

I remember laughing aloud at this…

… and then, abruptly, I stopped laughing.

I understood.

Understood how easily one can slip into those spiral arms of depression, like plummeting into the gravity well of an especially dark galaxy. Anyone who’s ever struggled with true depression comprehends this, too. Rewatch the episode. Listen to what he says.

I was more than a casual fan of Bourdain. From the baptismal font of No Reservations I devoured every installment of his other shows. I read Kitchen Confidential over a weekend, had some lunch, and picked the book back up for an immediate reread.

The man could write. By any reasonable standard, he was a truly gifted writer whose prose was simultaneously informative, funny, fearless, and brutally honest. The Bourdain that comes across in his books, and to an extent in his shows, isn’t just a moody, grim, grizzled chef and determined traveler. Despite his famously prickly exterior (or perhaps because of it) he was first and foremost a passionate guy. Passionate about food, about life, about people, about the moment.

In Kitchen Confidential, he relates how he transformed from a picky eater to daring culinary pathfinder. While on vacation with his parents and brother in France, he volunteered to try an oyster freshly plucked from the sea-bottom:

“It tasted of seawater… of brine and flesh… and somehow… of the future. This, I knew, was the magic of which I had until now been only dimly and spitefully aware. I was hooked…I had had an adventure, tasted forbidden fruit and everything that followed in my life–the food, the long and often stupid self-destructive chase for the next thing, whether it was drugs or sex or some other new sensation–would all stem from this moment.”

Anthony Bourdain was an adventurer. I’d been obsessed with adventurers my entire life, from the fictional exploits of Doc Savage and Indiana Jones to the real-life exploits of Howard Carter and Richard Francis Burton (Bourdain himself was obsessed with collecting Tintin comics as a boy). The man was an adventurer of the Burton school: irascible, tough, dark-eyed and vaguely dangerous… yet at the same time, smiling contently as he encountered a new taste among strangers coming together in a temporary family.

Sure, he was grim and pensive, and much of what he saw and heard on his worldwide jaunts must have added to that, like star-matter accumulating into the accretion disk of a black hole. Yet he was sensitive and receptive and sympathetic and eager to connect. Anthony loved the people he met. You could see it in his smile, in the misty look that came over him as he shared in dinners and asked about their lives and perspectives.

Parts Unknown and No Reservations and A Cook’s Tour had a way of diving straight into things without sermons or preconceptions. Bourdain’s visit to Iran is a great example: his upfront discussion of the crackdown on freedom of speech and the cruelties of Khomeini’s brutal regime contrasted suddenly with the Iran of today, where a woman in a hijab is bowling with friends in playful tribute to The Big Lebowski. “Down With America” posters contrast with grinning street-side vendors selling stars-and-stripes bikinis and flashing that true global language: the peace sign. And all this followed by the chilling epilogue highlighting how journalist Jason Rezaian and his wife were later arrested (and convicted of “propaganda against the establishment” after spending time talking with Bourdain on camera.)

His sense of humor had a razor edge. I can’t tell how many times I’d guffaw while reading tales of his culinary adventures. Laughing in public, laughing until tears sprang from my eyes. And I remember thinking, “This guy is one of the great ones.”

And now that he’s gone, the tears are there again. Bitter, anguished at his loss. Thinking back to all those brooding moments on his TV shows. To that moment in Sicily. To those contemplative moments glimpsed while he was hugging a beer, staring off into the past or future or ever-troubling present.

To the moments we never saw. The ones that were his alone, when the camera wasn’t rolling and his author’s pen was not in reach.